I’ve been thinking about Elizabeth Bishop’s poem The Man-Moth, which is a really interesting poem but also has interesting origins: A typo from a newspaper- the writer meant to use the word mammoth. “The misprint seemed meant for me,” she later explained.

Inspiration is a slithering thing – you never know where it might be and when it might strike.

And so, the man-moth was born.

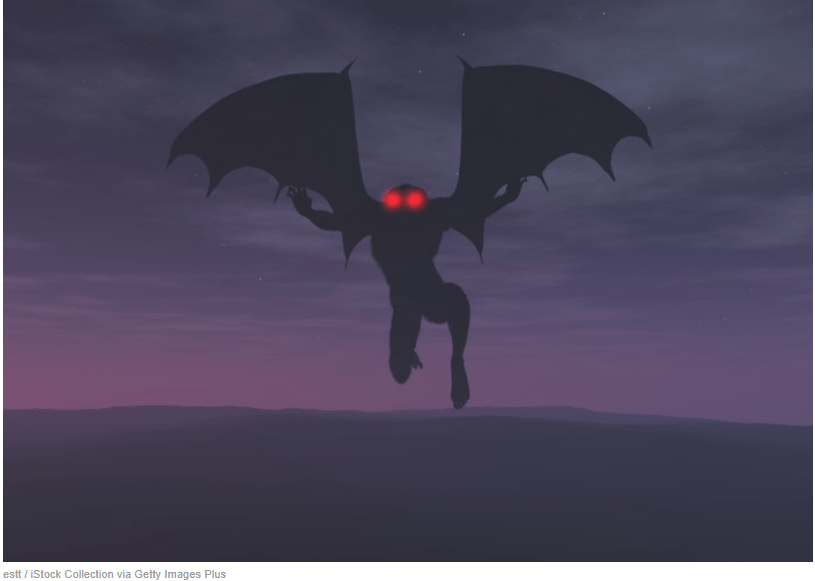

I taught this poem, years ago, to lethargic college freshman in a morning class in a rather soulless classroom (as most college classrooms are) and I used to to dip them into the world of imagery. It was written in the 1930s, and while a lot of images transfer nicely to the world of today, I like to imagine an early 20th century urban landscape. Something dark and noir-ish.

It opens like this:

Here, above,

cracks in the buildings are filled with battered moonlight.

We’re high up. We’re in a city. The battered moonlight immediately gives you an image of something gritty. I always imagine the action in this poem happening in black and white, like an old movie. It’s not intimate – it’s expansive and immediately feels lonely. It’s night time.

The man-moth climbs to the moon because He thinks the moon is a small hole at the top of the sky, proving the sky quite useless for protection.

I like the first half of that sentence. The poem is a bit awkward in places – not a surprise that it was written by a young poet, but it’s also brilliant, and I have a great affection for it. For what it represents, this man-moth climbing his way to the moon. Feeling out of place. Scared. Alone. Bishop was living in a big city, trying to make her way, and it was the 1930s, and she was a woman.

The man-moth is trying to make his way, too. Every night, he goes:

Up the façades,

his shadow dragging like a photographer’s cloth behind him

he climbs fearfully, thinking that this time he will manage

to push his small head through that round clean opening

and be forced through, as from a tube, in black scrolls on the light.

(Man, standing below him, has no such illusions.)

But what the Man-Moth fears most he must do, although

he fails, of course, and falls back scared but quite unhurt.

We get contrast here – from this dark urban landscape, from his shadow, to imagining his head popping through a sort of tube where he will burst into the light. It doesn’t work, of course, but he’s unhurt, and most of all – what he fears most he must do. I know enough about Bishop to hear her voice breaking through here.

The poem changes the more you know – when you learn that the city referenced might by NYC, and that Bishop didn’t have the greatest experience there, the poem feels prophetic in its darkness and sense of fear.

I like poems that go from vast to intimate, like this one does. From an image of battered moonlight, to the description of the man-moth, to his nightly journey to find the hole in the night, and finally to the creature himself. To his eyes. To his hands.

It ends by drawing the reader in, not just to the scene, but into the man-moth’s presence, to receive from him (if you do things right) a single tear he sheds which sometimes he drinks, but sometimes (if you watch him closely enough) he hands over – a tear which is “cool as from underground springs and pure enough to drink.”

That’s not only a light ending, it’s an intimate one. We’ve been with him, watching him. We know about his secret compulsion, about how he must try to get to that small bright hole night after night. And now we see him, we look into his eyes, we hold his gaze, and he gives us something very intimate. Something that is his only possession, something that he’ll swallow himself – unless you watch him.

And then, if you’re vigilant enough, you may receive.