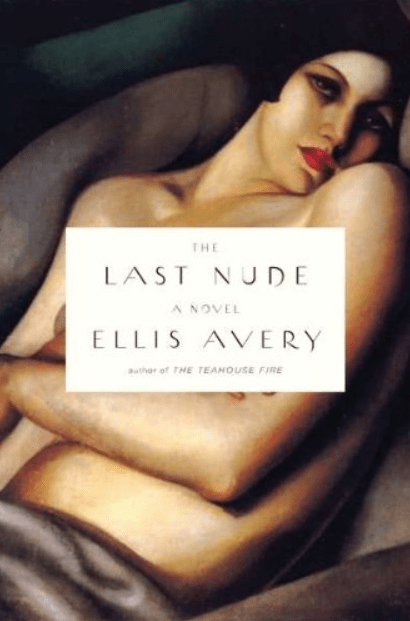

Ellis Avery’s The Last Nude paints an intoxicating picture of 1920s Paris – its art, its women, the haves, the have-nots, and the dangerous glamour of being desired. For queer readers, it’s a novel that both seduces and unsettles, capturing the way infatuation can swing into self-delusion.

The first section of the novel is, in my opinion, the stronger of the two. Young Rafaela Fano – runaway turned prostitute turned model and muse – feels wholly authentic as she escapes an abusive family situation and stumbles into the Parisian art world with a mix of hunger and innocence that’s instantly relatable. Her relationship with the famed painter Tamara de Lempicka* unfolds with the tension of an erotic apprenticeship: part love story, part power play. Avery’s prose glows here, especially in Rafaela’s awakening desire. Tamara is magnetic but opaque, and Rafaela’s slow realization that she has fallen for someone whose motives she doesn’t fully understand gives the novel its emotional core.

Mild spoilers ahead…

A quieter but equally devastating subplot involves Rafaela’s roommate, who becomes entwined in an affair with a married man. Her insistence that he’ll leave his wife mirrors Rafaela’s own refusal (or perhaps inability) to see Tamara’s true motives for what they are. Through these hopeful but ultimately naïve women, Avery deftly explores how longing can become a form of blindness and how unequal power dynamics in relationships don’t often favor the young.

The second half, set decades later and told through the voice of an aging Tamara, is more divisive. It certainly offers poignancy. Tamara haunted by memory, by what she took and what she lost – but it also feels emotionally distant and ultimately unsatisfying. For some readers, the shift deepens the tragedy; for others, it fractures the intimacy the first section built so carefully. The reflective tone doesn’t quite match the youthful fire of Rafaela’s voice, and the balance between nostalgia and regret never fully lands.

It also leaves parts of Rafaela’s story untold, her voice fading into a mystery, leaving the reader wondering as desperately as Tamara what ultimately happened after the novel’s big plot twist. Only small details are revealed, and the reader will piece together possibilities along with Tamara, who seems unable to let go of the memory of the young woman she once sacrificed and insists she never loved. Perhaps that was Ellis’s point, but for a reader with an emotional investment in Rafaela, it’s a bit of a letdown.

Still, this is a striking queer novel about power, art, and the price of being seen. It’s less a straightforward romance than a meditation on desire’s aftermath – what happens when a muse outgrows her painter; when a girl whose body is her only asset learns the difference between appreciation and exploitation.

Even with its uneven structure, The Last Nude lingers in the tension between self-discovery and heartbreak, and in the lingering question of who gets to turn pain into art. Rafaela may disappear from the canvas, but the echo of her voice – young, yearning, and finally self-aware – remains the novel’s truest masterpiece.

*While Rafaela Fano is a fictional character, Tamara de Lempicka is an historical figure. You can read more about her here.