In Victorian literature, women often became the canvas for society’s unspoken fears and desires. The era was obsessed with controlling female sexuality and codifying gender roles, yet also fixated on the possibility of what might happen if those boundaries were crossed. Morality fiction thrived, and morality tales were even applied to history books in how historic figures were portrayed and judged. Fact was less important than the lesson.

But the truths a culture tries to bury have a way of resurfacing. What’s repressed rarely stays dead; it resurrects itself, transformed. In that sense, the Gothic’s ghosts and revenants were never just symbols of fear – they were the echoes of feelings that polite society refused to name.

Writers could project forbidden emotional and erotic energies onto women because the culture already treated women’s interior lives as mysterious and unimportant, thus a safe site to explore transgression without threatening the moral order too directly. It was a paradox at the heart of Victorian thought: women were seen as the moral anchors of society, yet their virtue had to be defined, supervised, and protected by men. They were entrusted with preserving purity but denied the complexity or authority that moral stewardship should have given them.

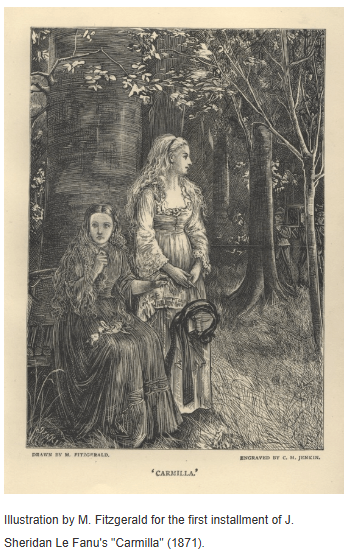

Le Fanu’s Carmilla sits right at the center of this paradox.

By giving his vampire story to two women, he could dramatize passion, dependence, and even obsession in ways that would have been too dangerous and too revealing if written between men. Female intimacy could be coded as strange but natural, innocent but excessive. It could titillate readers while giving the author plausible deniability: this isn’t about sex, it’s about corruption, hysteria, or supernatural influence.

But that same framework allowed for moments of genuine emotional realism that male characters of the period rarely achieved. Because women’s affections were trivialized, they could also be portrayed with vulnerability, longing, and tenderness that slipped past censors’ notice. The result was a story that could simultaneously reinforce patriarchal fears (“wayward women must be punished!”) and subvert them (“but look at the beauty of what they share before that happens…”)

For queer readers, especially women and gender-nonconforming people, these coded narratives became lifelines. They offered glimpses of feeling, connection, and recognition hidden within the cultural machinery of repression. Le Fanu probably never imagined that Carmilla would one day be embraced as a queer classic. But the emotional authenticity he allowed between Laura and Carmilla – their yearning, their secrecy, their tragic intimacy – gave later generations a point of identification.

Where Victorian critics saw pathology, queer readers saw possibility. They understood that beneath the Gothic trappings was something more universal: the ache of loving someone you’re told you shouldn’t, and the horror not of the lover, but of the society that demands her destruction.

In the late 19th century, depicting erotic desire between men was not just taboo – it was criminal. Writing openly about it could end a career or a life (ask Oscar Wilde). Female same-sex intimacy, by contrast, was largely invisible to the law and to polite society. It was treated as a curiosity, a phase, or at most an excess of feminine emotion. That blind spot gave male authors room to experiment with dangerous ideas under the guise of feminine sensitivity.

Le Fanu could explore themes of longing, secrecy, and possession using women as emotional stand-ins, letting him write about forbidden desire while maintaining moral cover. The female vampire became both scapegoat and screen: her queerness condemned, her power eroticized, her hunger framed as both predatory and irresistible.

But in the spaces between those contradictions, something true broke through. Laura and Carmilla’s bond pulses with tenderness and grief, with the ache of intimacy that can’t be named. The fact that the story ends with Carmilla’s destruction doesn’t erase that tenderness; it heightens it. She’s destroyed not because she is monstrous, but because society insists she must be.

Victorian culture was a master of double-speak – saying one thing while signaling another. Literature thrived on suggestion: the unsaid was often more charged than the explicit. In that tension, queer readers learned to read differently – to find meaning between the lines, to recognize the pulse of truth under layers of moral varnish.

That’s why literature was often used in queer communities of the past as a coded way of communicating identity and feelings.

In Carmilla, they found a mirror: a story that named their desire even as it condemned it. Queer readers across generations have reclaimed her, reinterpreting her from tragic villain to sympathetic antihero, to a figure of endurance and defiance. In modern retellings, Carmilla survives. She loves without apology. The monster becomes the muse.

This is a story thatreminds us that queerness has always existed, even when it had to hide behind metaphor. The Gothic tradition, for all its repression, often gave forbidden feelings form and voice. It gave us a language of secrecy, yearning, and resistance that queer storytellers still use today.

Le Fanu may not have written Carmilla to humanize queer love, but that’s what his story accomplished anyway. In giving shape to forbidden desires, he opened a door that later generations walked through more boldly.

The story endures because it tells a truth the Victorians couldn’t admit: that love itself was never the horror. The real horror was the world that demanded its erasure.

Every generation finds new language for what came before. When we return to stories like Carmilla, we aren’t just reclaiming what was hidden in plain sight; we’re acknowledging how long the longing has been there. The past speaks in whispers; we hear it, reinterpret it, and add our own voice to the chorus.

That, too, is a kind of resurrection.

Further Reading:

Carmilla by Sheridan Le Fanu is now in the public domain.

Foundational Texts:

Nina Auerbach, Our Vampires, Ourselves – discussion of how Carmilla prefigures modern depictions of female vampires.

Lillian Faderman, Surpassing the Love of Men – explores female romantic friendship and coded same-sex intimacy in 19th-century culture.

Christopher Craft, “Kiss Me with Those Red Lips” – discusses gender and sexuality in Gothic fiction.

More Recent Scholarship:

Sharon Marcus, Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England – relationships between Victorian women.

Paulina Palmer, The Queer Uncanny – how the uncanny represents queerness in many different forms.