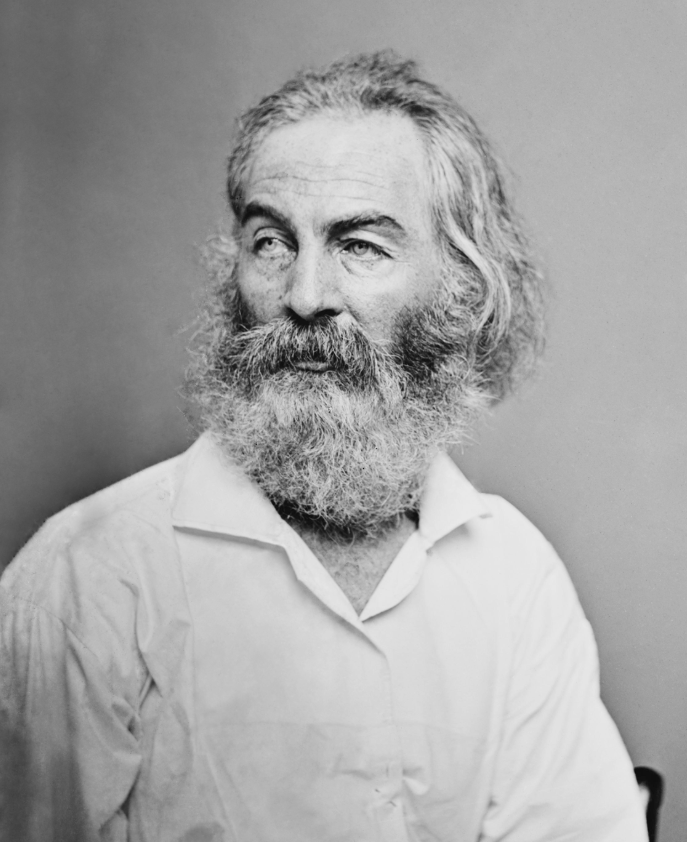

I’ve been rereading Walt Whitman recently. He’s a good autumn read – heavy nature imagery and blatant queer joy, which is what I tend to crave this time of year.

I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised and naked,

I am mad for it to be in contact with me.

Walt Whitman was certainly a poet of nature, but he also wrote extensively about love – familial, erotic, divine.

Infused in his words of love is touch and the sensual. He wrote about the shape of a shoulder, the smell of sweat, the curve of a hip, water droplets on a beard – what he saw as the living, breathing miracle of the human body. While he particularly exalts the male body, he writes about women, uplifting their bodies and their purpose (as understood in 19th century society). He writes about white bodies and Black bodies and Indigenous bodies, old bodies and young bodies, able bodies and wounded bodies and, most importantly, bodies that worked. Bodies that got dirty. Bodies that were often exploited or overlooked.

He didn’t flinch from the messy stuff – the dirt, the sweat, the wounds, the fluids – because to him, that was intermixed with the divine.

So was queerness.

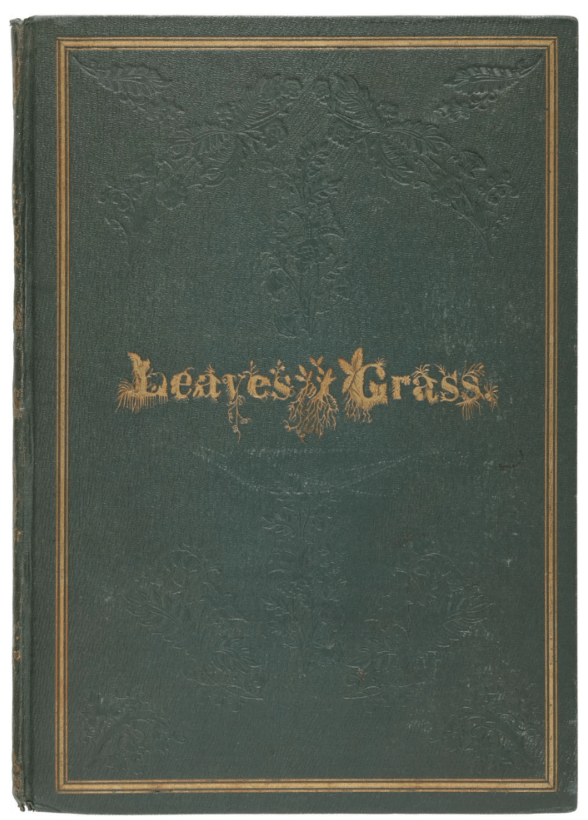

In Leaves of Grass in particular, Whitman celebrates queerness not as something shameful or hidden, but as something both radiant and ordinary, part of the beating pulse of the world. His poems hum with the energy of bodies in motion – male, female, old, young, alive, dying, desiring, caring, working, resting. If he shocked his readers, it wasn’t because he was indecent, but because he was joyously unashamed.

Whitman believed the body was a scripture. He wanted Americans to see our bodies not as vessels of sin but as a means of connection, to each other and to the divine.

I would argue he’s part of the Transcendentalist family tree, even if he’s not formally classified as one. Like Emerson and Thoreau, he believed in the divine spark within every person, but he took that belief out of the abstract and into the flesh.

Where Emerson looked for God in the mind, Whitman found divinity in the skin. He wrote, “If anything is sacred, the human body is sacred.” He didn’t want to transcend the human body, he wanted to transfigure it. His vision was simple: the soul doesn’t hover above the body; it lives inside it, sweating, aching, working, desiring.

Whitman’s eroticism in that sense is political.

His Calamus poems, the most openly homoerotic section of Leaves of Grass, praise “the manly love of comrades” with a tenderness that goes beyond friendship. He calls this “adhesive love,” a bond between men that he believed could hold a fractured nation together.

For Whitman, same-sex/same-gender love wasn’t a deviation; it was a model for democracy. A country, like a relationship, survives through empathy and the recognition that another person’s body, pain, and longing are as real and valid as your own.

It’s astonishingly bold, even now, to turn erotic affection into a moral and civic principle. To love one another – to touch, to see, to care – becomes the foundation for freedom itself.

Though the Calamus poems often draw the most attention, Whitman’s reverence for the body extends to women as well. In “I Sing the Body Electric,” he celebrates “the female equally with the male.”

He describes birth, motherhood, and female sexuality with a sensuality rarely granted to women’s bodies in the 19th century – at least, not in a way that didn’t punish or moralize. Even when his gaze is undeniably male, it’s also full of awe:

I am the poet of the Body and I am the poet of the Soul,

The pleasures of heaven are with me and the pains of hell are with me,

The first I graft and increase upon myself, the latter I translate into a new tongue

I am the poet of the woman the same as the man,

And I say it is as great to be a woman as to be a man,

And I say there is nothing greater than the mother of men.

For Whitman, desire was universal. It didn’t belong to one gender, one orientation, or one form of love. What mattered was the physical fact of being alive, the pulse beneath the skin, the sensuality of being in the world.

He saw the erotic as the democratic: no body is beneath notice, no desire is beyond grace.

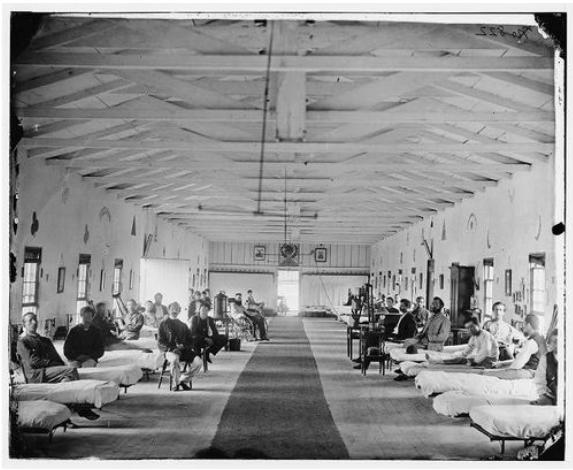

It’s often said that Whitman worked as a nurse during the Civil War, tending to soldiers in hospitals around the Washington, DC area. He had no formal nursing training; he was actually a tireless, dedicated volunteer, offering care and comfort to the wounded – sitting with them, talking and reading to them, listening to their stories, writing letters for them, supporting them through painful procedures such as amputations, and holding their hands as they were dying. He was a caregiver in a the truest sense rather than a medical practitioner.

Though many medical advances came out of this era, medical care of the era was often gruesome, as were the injuries suffered by wounded soldiers. The experience deepened Whitman’s understanding of love, loss, pain, and the physical reality of the soul. He wrote about dressing wounds, bathing broken bodies, holding dying men as they took their last breaths. There is tenderness in those lines – sometimes explicitly homoerotic, sometimes simply human.

It’s not that he was romanticizing pain; he was acknowledging that compassion lives in human contact. In those moments, his queerness, his spirituality, and his politics all meet. To touch another person’s suffering, for him, was a sacred act.

I do not ask the wounded person how he feels, I myself

become the wounded person…

He saw the divine not in heaven, but in the hospital ward – in the quiet intimacy of care. Some of the soldiers he cared for were boys or teenagers. Some were experiencing extreme mental health issues. Some had no other visitors and were totally alone. He gravitated toward the patients who were most in need of support.

Before the war, Whitman’s poetry is more erotically charged, an unabashed celebration of bodies. After the war, it takes on more of a tone of tenderness with a sense of mortality. Vulnerability and suffering become more present, but no less divine. Erotic touch becomes infused with the intimacy of caregiving. Perhaps there was more sorry than celebration, but there was more intimacy as well.

Whitman’s work is still radical because it refuses to divide the sacred from the sexual. He loved the body without apology. He celebrated physicality and desire as the language of democracy. He saw queerness not as an exception, but as a revelation of how interconnected we are.

It’s no wonder he made the moralists nervous…and no wonder he still does.

In an age where censorship is once again being justified in the name of protecting morality (read: upholding bigotry and misogyny), Whitman’s voice, urgent and insistent, cuts through the muck like sunlight: this is the body, this is the soul, and it’s the same thing.

He reminds us that shame is learned, not inherent. And that queerness, in all its longing and tenderness and flesh and contradiction, has always been part of the American landscape.

Select Sources and Further Reading

- Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass — especially the Calamus poems and Song of Myself

- Whitman’s Civil War writings — Specimen Days and Drum-Taps (available via Project Gutenberg)

- The Walt Whitman Archive — an exceptional resource on his queer readings and historical context (whitmanarchive.org)

- David S. Reynolds, Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography (1995) – a vivid look at Whitman’s influences and the world that shaped him. (An older work but still considered one of the authoritative works on Whitman.)

- Betsy Erkkila. Whitman the Political Poet and several other works. Here is a free version of Erkkila’s more recent book The Whitman Revolution: Sex, Poetry, Politics.