Every February 14, Americans buy roses, swap cards, book dinner reservations, and post heart emojis like it’s a civic duty. But Valentine’s Day didn’t start with chocolate boxes or candlelit restaurants.

It began with a martyr.

Possibly several martyrs. And along the way, medieval poetry, Victorian craft culture, and American industrial capitalism quietly reshaped it into the holiday we know today.

Here’s how it evolved…

Early Catholic Martyrs

The Catholic Church recognizes more than one early Christian martyr named Valentine. The two most commonly associated with February 14 are St. Valentine of Rome and St. Valentine of Terni. Both were executed in the 3rd century, traditionally during the reign of Claudius II.

Later legends claim Valentine secretly performed marriages after the emperor banned them for soldiers. It’s a romantic story, but there’s not a lot of historic evidence that it’s true. What we do know is that by the early Middle Ages, February 14 had been designated as St. Valentine’s feast day.

At this point, however, the holiday had nothing to do with romantic love. It was simply a saint’s day in the liturgical calendar.

Lupercalia

Many people also believe that Valentine’s Day evolved from Lupercalia, an ancient Roman festival that was celebrated on February 15th. The connection is possible, but Lupercalia wasn’t a celebration of love. It did promote fertility, included animal sacrifices, had its own priesthood. It was during Lupercalia in 44 BC that Julius Caesar famously refused the golden crown offered to him by Mark Antony.

Plutarch describes Lupercalia as a day when “many of the noble youths and of the magistrates run up and down through the city naked, for sport and laughter striking those they meet with shaggy thongs. And many women of rank also purposely get in their way, and like children at school present their hands to be struck, believing that the pregnant will thus be helped in delivery and the barren to pregnancy.“

Basically they ran around naked smacking people with pieces of flayed animal skin from the sacrificed animals. Odd as it sounds, this was a joyful festival, and not at all something meant to be violent or punitive.

Chaucer and Medieval Courtly Love

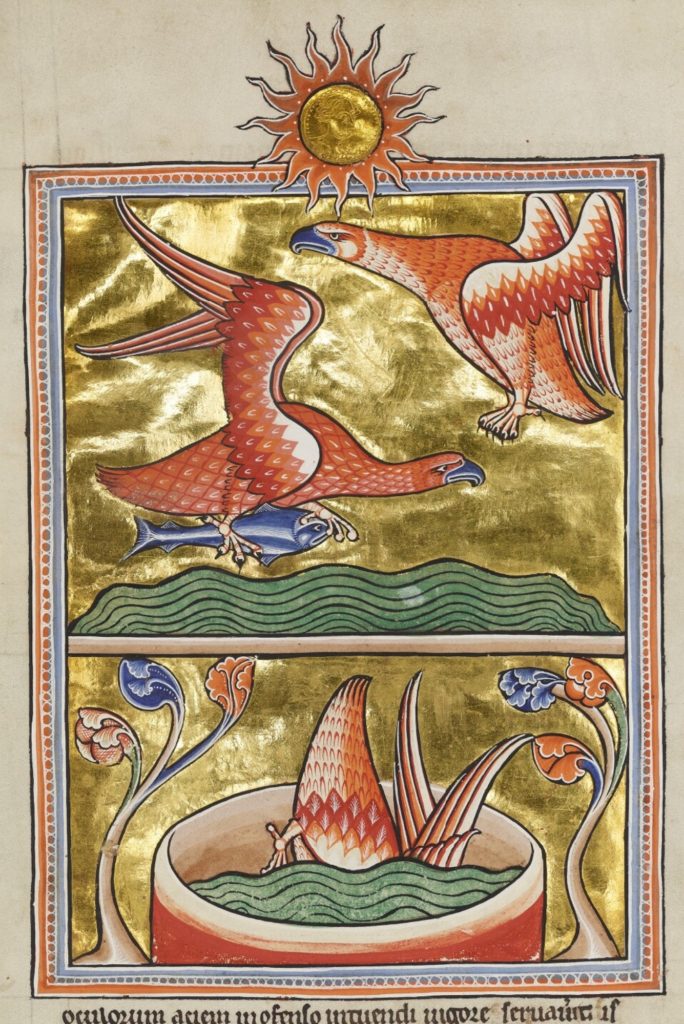

The romance connection between Lupercalia, the martyrdom narratives, and what eventually evolved into a commercial holiday appears to crystallize in the 14th century. In Parliament of Fowls, English poet Geoffrey Chaucer wrote that birds choose their mates on Saint Valentine’s Day.

In the years that followed, the holiday appears to have absorbed elements of medieval courtly love culture. Aristocrats began exchanging poems and tokens. Love, in this context, was theatrical, stylized, and often idealized.

But this was still a niche, upper-class custom — not yet the mass ritual we recognize.

Evolution of the commercia Valentine

By the 1700s in England, exchanging handwritten valentines had become popular. These were often folded notes decorated with hearts, flowers, or romantic verses.

As English customs crossed to North America, so did Valentine traditions. In early America, people wrote handwritten love notes. Postal reforms in the 19th century made mailing cheaper and more accessible, and industrial printing lowered the cost of decorative cards.

And Americans embraced it. Valentine’s Day truly transformed in the United States during the 19th century.

In the 1840s, Esther Howland of Massachusetts began mass-producing elaborate lace-paper valentines inspired by English designs. She’s often called the “Mother of the American Valentine.” Her cards were intricate, sentimental, and wildly popular.

By the late 1800s, factories were producing ready-made valentines at scale. Romantic imagery — cupids, roses, hearts, lace — became the standardized symbols of mass-market love. The holiday shifted from handmade intimacy to commercial ritual.

In the early 20th century, companies like Hallmark expanded production nationwide. Chocolate makers, florists, and jewelers followed suit. Eventually, Valentine’s Day became one of America’s most profitable holidays.

One particularly American evolution? The classroom Valentine exchange. Does this still happen? I remember doing this in school with small store bought valentine’s cards, about the size of baseball cards. By the mid-20th century, children were bringing small cards to school for every classmate. Some schools, like mine, even had parties for students to exchange cards and have themed treats. The holiday expanded beyond romantic love into friendship, family, and general affection.

February in much of the United States (and other places) is (or, at least, used to be) cold, dark, and emotionally long. A holiday centered on choosing someone has powerful appeal. Underneath the commercialization, the core idea remains surprisingly medieval: connection matters. In winter especially.

Valentine’s Day survived because it speaks to something durable, even if it now comes wrapped in cellophane and glitter.

Queering the Valentine

For queer folks, Valentine’s Day has a slightly different meaning.

Valentine’s Day has always been about visibility. In medieval court culture, love poetry allowed aristocrats to stage desire in stylized, semi-performative ways. It wasn’t just about romance, it was about declaring their romantic attachment in a public forum.

But public declarations of love have historically been policed. When sodomy laws were enforced in England and later in colonial America, romantic expression between same-sex partners could not be publicly ritualized. There were no sanctioned “valentines” for queer couples. No feast day that legitimized their bond.

The very fact that Valentine’s Day became a cultural ritual would have been problematic for queer people. Rituals signal belonging. But for centuries, queer love survived in coded letters, ambiguous language, shared books, and rumor networks. In that sense, Valentine’s Day sits awkwardly at the intersection of publicly and religiously sanctioned affection, forbidden affection, and the politics of who is allowed to say “I love you and I choose you” out loud.

Unfortunately, that tension still lingers,.

As does tension around the loss of personalization. When industrial production scaled the holiday, something subtle happened. Romantic expression became standardized. Pre-written sentiment. Pre-illustrated hearts. Pre-approved tone.

This narrowed a celebration of love and affection into something only for heteronormative couples, for monogamous domesticity, or for market-friendly affection.

But love has always been much more volatile than that.

Queer communities have often expanded the meaning of Valentine’s Day and the idea of choosing beyond a day and beyond even just romantic pairing, and into chosen family, mutual aid, radical care.

When queer couples began openly celebrating Valentine’s Day before marriage equality, that was quietly subversive. When interracial couples exchanged valentines in eras when their marriages were illegal, that was radical. A holiday that asks, “Who do you choose?” is political in a society that has historically dictated the proper, acceptable answer.

Valentine’s Day is Political

Valentine’s Day began as a martyr’s feast — a memory of someone executed for defying authority. Over time, it became a celebration of pairing. In America, it became a retail machine.

But at its core, it remains about declaration.

To love publicly is to insist that attachment matters. To write love down is to refuse erasure. Maybe the holiday survives not because of candy hearts, but because humans are wired to resist isolation. And because every year, in the dead of winter, we practice saying, “I choose you.”

Which is a political act, whether we admit it or not.